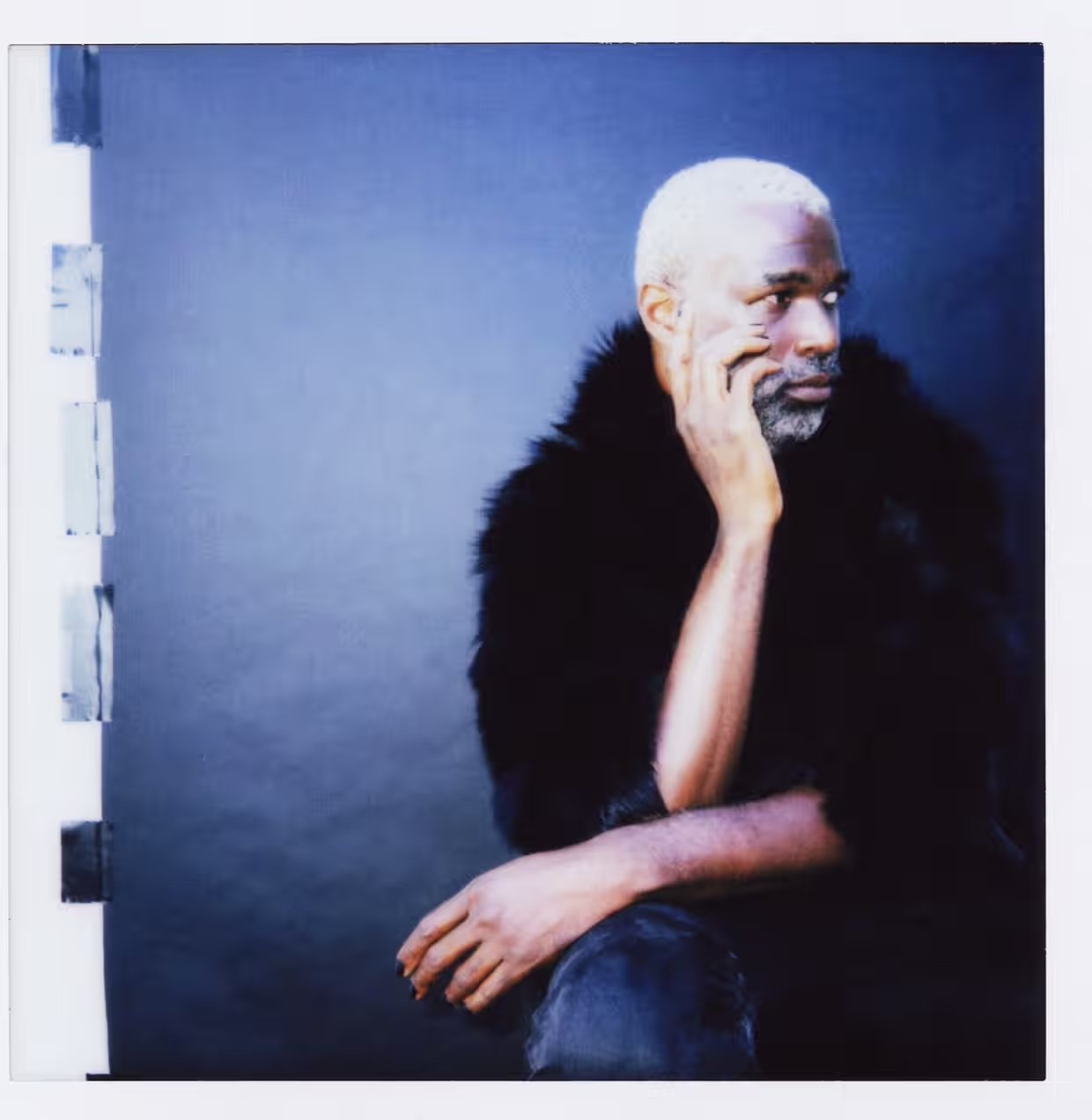

Tunde Adebimpe in conversation with Malcolm-Aimé Musoni

Xaviera Simmons

With a storied career that includes being one of the original animators on MTV’s Celebrity Deathmatch, co-founding the groundbreaking indie rock band TV On The Radio, and starring in movies like Rachel Getting Married, Spider-Man: Homecoming, Twister, and TV shows like Lazur Wulf, The Girlfriend Experience, and Star Wars: Skeleton Crew, Tunde Adebimpe has spent decades shaping culture.

Now, 21 years after the release of TV On The Radio’s debut album, Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babe, Tunde has released his first-ever solo album, Thee Black Boltz. Created in the aftermath of the unexpected 2021 death of his closest friend, his sister Jumoke. The indie rock album-with as much zigg as zagg, is Tunde at his most vulnerable as he processes that grief and a world careening towards violent authoritarianism. On the album’s only acoustic ballad, “ILY,” he sings to his late sister, “Let's wait for the stars to shine so maybe we can see it better / And we could take the time if only just for one more day / Yeah, we could glow bright as the sky when the sun hits the sea / And, oh, I love you.” Whether you have lost someone or not, you feel Tunde’s pain. It’s a gut-wrenching moment on an album filled with many highs and lows. Longtime fans of TV On The Radio shouldn’t be surprised, though. As the principal songwriter of the band, Tunde’s poetic lyrics helped cement the band as one of the most imaginative bands of their generation. But with Thee Black Boltz, Tunde firmly and officially takes center stage, revealing all of himself.

Our founder and editor-in-chief, Malcolm-Aimé Musoni, hopped on a video call back in February with the multi-hyphenate for a candid conversation about his new album, grief, and the importance of his sketchbook.

In the past year, there’s been the re-release of Desperate Youth, Blood Thirst Babes, a TV On The Radio reunion, tour, and now your first solo album. How does it feel to be back at it and ramping up in such a big way?

It feels great. Getting back into it feels kind of like, oh thank god. There was a lot of not-so-much downtime, but just a lot of time where, for whatever reason, it could not be in a creative flow. The band had put things down probably six months before the pandemic hit. It was just kind of like, I don't even know if we're going to do anything anymore. It's been a very good run, and we all need a break at least. That was already kind of not a thing anymore. And then the pandemic, and I was just like, What am I doing? There was no acting stuff happening, even though acting is still, on a certain degree, a matter of waiting around for someone else to need you. But none of that was happening. There was no touring happening. There was nothing. A lot of sources of income. [Laughs] Gone. It was a very scary theme park ride. I feel great and grateful to be having it come out. The responses to things have been positive and heartwarming. It’s been very cool.

In a recent interview with DIY magazine, you said, ‘I had a bunch of demos in 2019 and decided to shop them around and see who might be interested in putting them out aaaaand nobody wanted to do it. “I definitely had a big moment of, ‘Ohhhh right! All of that cultural capital I thought I’d amassed in the early 2000s, maybe that’s just… done!’” For so many artists these days, they spend their time making music, and that's one thing. But to keep their audience engaged, they also have to spend their time feeding the beast of celebrity: their life becomes content. You have a child and you have a wife. There aren’t a lot of photos on the internet of you all together: you haven’t fed the beast in that way. Coming back with this solo project–your first solo album ever–was there ever a feeling of Oh, if I want to get these major labels’ attention, I need to feed the beast. Or have you always been dead set on just making the music?

I feel like if I knew how to feed the beast [laughs] at any point in my life…[laughs] I’m so grateful for the position I’m in as an artist. And by that I mean I am, by and large, making what I want to make. For better or for worse. I'm not directing it towards a certain market or type of person. I know that most of the music and art that I encountered that inspired me is not laser-focused at like I know that this Nigerian-American kid in Allison Park in Pittsburgh, I'm gonna get him with punk record, or I'm gonna get him with De La Soul and the Chili Peppers. I don't know how to do that, and I feel like anytime I have been in a situation where anyone I'm collaborating with is just kind of like, we gotta aim in that direction, it doesn't feel great. And I know there are people who are so good at that…

We love that for them. We love people who can do that. Go off! [laughs]

[laughs] We love people who can do that. We love people who can own homes. [laughs]

Multiple homes at that. [laughs] In different countries. [laughs]

[laughs] Multiple homes, a home. [laughs] I don't know how to do that. I feel really lucky that I've put out the stuff that I've wanted to and, for better or worse, that anybody cares. It means so much to me that… I mean, as weird as this might sound…you're the person that I wish I'd met in high school.

You’re the person I wish I met in high school! Where were you when I was in high school?!?!

I've asked that question so many times, but you know what? That's the thing about having done this. It's this weird Message in a Bottle through time, and it finds who it's supposed to find. I was in a Staples and there’s this beautiful queer Black man who was wadering around. I’m in the aisle looking for stickers, and he came up to me just like, ‘Excuse me. Are you Tunde?’ I was like, ‘Yeah.’ He’s just like, ‘I just wanted to say, I’m such a fan, and thank you.’ And I was just like, ‘Where the fu-were you when I was in high school?’ With exceptions, those were the people I fell in with—the punks, and all the marginalized people. It was a very odd thing to go from a small community in Pittsburgh where it was more the punk scene that was anti-racist—before that had a name, was just inclusive, anti-fascist—they had queer kids in it. It was weird to go from there to New York, where that was also the case. And then to kind of get older and when the band got bigger and more–for lack of a better term, normies liked to listen to it—to just realize, Oh shit. It's so strange to have grown up with this all around you, and then to get into the larger world and be like, I'm still in a situation where the entire world is not accepting and acknowledges that everybody's a fucking human being and there’s so many different ways to be and they’re all valid.

Xaviera Simmons

In 2020, you released a solo song, “People,” and divided the proceeds between The Southern Poverty Law Center, The ACLU, and The Movement for Black Lives. One of the first lyrics of “Magnetic,” ‘In the age of tenderness and rage,’ was taken from a sign that a young woman was holding at a protest. On “Crying” from the 2008 TV On The Radio album, Dear Science, there’s a line where you sing and allude to what has been going on with Palestine and Israel. There’s a political nature that’s always been present in your music. I find this interesting because with so many artists, espeicifcally Black artists, they might be on some radical or leftist shit when they’re young. But like most people, as they get older, they tend to become more conservative. There’s something about getting older that encourages and allows conservatism to latch onto you. You're still making music that has a political nature to it: it's not lucrative to do that. Why does that still feel like something necessary and important for you to do?

I feel like I was just raised that way. I remember being in New York and having a very weird moment where I went to the zine store called See Here in East Village. It was great because I had a zine that I wanted to sell, and I’d made this comic. See Here is this legendary place: you go there, you take a bunch of your zines, you can sell stuff on consignment, you can do trades. It was a great store. There were all these things that I’d only heard of that I thought I would never get my hands on: comics, zines, records, all of that stuff. And they also had free zines by the door. And so I went over to the door, and there were a couple of things there, just like photocopied–stapled on the side. I picked one up, and it was just white supremacist shit. I was just kind of like, oh. And then there was another one there. I realized in about a month that–as is often the case—this is just written by an idiot. People were just scared, small, and full of shit. I grabbed all of those free zines, and I put them up on the counter, and I was just like, ‘I'm gonna take these two,’ just to see what the owner’s expression would be. And he was just kind of like, ‘Okay,’ and I was just like, ‘It's weird. You have this shit up next to the free zines, with all this kids shit too.’ And he's just like, ‘Whoa, what is it?’ And I was just like, ‘It's Nazi shit.’ And he was just kind of like, ‘Well, you know, it's like this punk sort of thing.’ And I was like, ‘All right, that's cool.’ So I left, and I threw them in the garbage. I kept two of them as a cultural studies sort of thing.

My dad was a psychologist, psychiatrist, and social worker in Pittsburgh. Most of my dad's career was dedicated to teaching psychologists and psychiatrists that a person who is not from this country–an immigrant should be judged by a different set of criteria. And also, he’d say that Black people and people of color–you have to take into account their cultural cosmology. Someone might be talking about something that refers to a very specific religious situation from their background. That needs to be taken into account, he said. Which is why we need more black psychiatrists, and why we need more people doing community outreach. He was dedicated. The other part of his life was trying to teach psychiatrists that racism actually had an effect on black people. This is the 80s, and he was giving lectures about how that was a real thing. And he had all of these people just be like, ‘Well, it's just not really a real thing. ’ It's just like, What the fuck are you talking about? I remember calling him and being distraught. I was like, ‘I can't believe that these magazines are here in New York.’ And he basically was just like, ‘There are people who are working on that. There are people who are after hate groups. There are people who are doing this, doing that.’ And that gave me a sort of sense of security, but also made me want to look more into that kind of thing.

In my heart and soul, I don't want anyone to feel a fear of being themselves. I don't care who the fuck you are. Who are you to deem someone not human and spend your fucking life trying to rail on them? What a waste of your life, too. But as far as giving to organizations that are standing up for black people, people of color, trans people: I can’t not think about that stuff. I feel like making art and music is such a privilege, and it's like an antidote to all of that. That shit saved my life, it saved the lives of many of my friends.

Xaviera Simmons

I want to get back to the album. I listened last night, I was off a 150 mg of THC edible. I had an amazing time. I said, Oh this is real music. Can you explain the title? What are Thee Black Boltz?

I was at a certain point, really deep in grief—it’s a metaphor. Surrounded by these dark clouds, they obscure your vision. You can't see in front of you. You don't want to see in front of you. But then those coming together—whatever positive and negative electrons, mash up and a bolt of lightning can come through—which is a bolt of inspiration–which can illuminate the landscape and how much more there is around these dark clouds. It's also an appreciation for these dark clouds, for bringing you into this moment that yields this inspiration.. It's that, and also, in my head, too, for some reason: it also became a persona. Thee Black Boltz was just kind of this like extra thing that is a part of me– the product of this teenage dream of being in this–I love the idea of a persona to help you go through something. David Bowie and The Thin White Duke. Not so much Garth Brooks and Chris Gaines. Not so much in that direction.

In my research, I learned that you have these notebooks that you create before your projects. They have words, illustrations, and ideas. We’re living in a world where everything is digitized. As a child, I wrote everything by hand–I would write songs pen-to-paper and sing them over and over to memorize the melody because I had no way to record it. Then, when I wanted to be a fashion designer, I bought a book from Barnes and Noble on how to write a business plan for a fashion company. I wrote an entire business plan–pen to paper. I would never do that now. I almost exclusively create via my laptop. I know I shouldn’t, but it’s easier. This is a two-parter: When did this become a practice? And why continue to do this, pen-to-paper?

I've always kept sketchbooks since I was probably 13 or something. I was always just drawing, not so much writing. I wanted to be a cartoonist and a comic artist, so I always had these books around. And I think I started writing in my early 20s. Keeping journals, but also writing poetry that might work for something. This is even before I had an idea that I would be doing music. It's a way to organize my thinking, and I feel like doing it freehand on a piece of paper is just faster for me. When I’m typing something, I don't retain it. And exactly what you were saying about writing stuff down. When I was in New York, before I had a phone, before I had a laptop, it was exactly that–eventually, I got a little dictaphone. But I'd be walking around the city, over the bridge, humming this tune. Because I was like, I can't fucking forget this. I can't, I gotta remember this until I get to the four track. I can't forget it. I think that’s great. There's so much now that I just don't retain. And me being on a computer doing anything creative—outside of recording, just takes too much time. And there's so many distractions available to you, there's so many portals.

You experienced some loss while working on this project. There’s this all-encompassing part of grief that is hard to comprehend until it happens to you. My mom died in 2015, I was 17. Even though she had been sick for a while, it still felt like I got run over by a truck. I thought I'd feel like that forever. I And then one day I didn’t. I found a new norm. You’ve said that making this album was like building a shrine to your sister and people who have passed in your life, to say thank you. Because Thee Black Boltz is personal, did you ever consider not releasing this? Just keeping it as demos for yourself?

I’m sorry to hear that, that’s a very rough experience to go through and it is like that, you feel like that’s it, you’re suck in this sad nightmare forever, and then gradually it just becomes something different, a feeling that is part of you but isn’t dominating your day to day life as much. It can take a loooong time. Grief therapy was and is extremely helpful for me, and having a place to put all of those feelings, writing, art, the things that became this record, doing the things that these people who are no longer here would want me to be doing is helpful. I never thought of holding on to any of this just for myself, I think one of the functions of art making/music making is to get that stuff away from you and kind of construct a scale model of the feeling or situation and then you can hand that off to the universe and then it’s for whoever finds something in it for themselves. There’s that quote that will pop up in how-to books about writing: “The personal is universal”, and I don’t know how much of those experiences come through in these songs, but I hope that they are helpful or a comfort or a respite or a joy for anyone who might need that.

“Somebody New” is my favorite song on the album. Production-wise, it’s very upbeat and makes me feel happy. Lyrically, it seems to be telling a story of push and pull within a relationship. I think you say, ‘Can’t seem to shake you, got no complaints. I just want to be somebody new. Is there nothing in the world we can do about this? Heavenly vibration coming through. You move like a storm cloud. Rolling in fast.’ How did that song come together?

So glad you’re into it! I like that one a lot too. The line “I just want to be somebody new” was something that was floating around in old song sketch with bunch of other random babbled words in it, and one day my producing partner Wilder was messing around putting synths on this kind of pop-y house track he was making for something else, and I took the old phrase and tried it out on that and it worked and we kept it for the record / ourselves. It ended up being more New Order than house-y, but it definitely lends itself to and needs at least 10 house remixes. If anyone reading this feels the urge, please make it so.

It could definitely be about the push and pull of a relationship, I think it’s an all-purpose reset song, just for when you’re sick of yourself, of a situation, of the world. Could work as a mindset and heart set recalibration, and I think that maniacal dancing, alone or in a room full of people, or (even in your mind)is a reminder that you’re alive and can potentially activate a change of emotion, of viewpoint, and potentially an entire situation. An uplift.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.